When is it ok to talk about race?

Race should be on the table for open conversation in the classroom

April 28, 2021

“You and I are the same,” . . . “We are all equal,” . . . “I don’t see color.” These are just a few of the most common, but harmful sayings in American workplaces, social scenes, and classrooms. These seemingly insignificant words are so widely used that the people who use them fail to realize how destructive they can be to people of color. What is most alarming is that these words are spoken in passing among students and teachers across the country everyday. Racial bias has become an increasingly dire issue in Amercan society, and the conversation must be brought to the classroom in order to create an equitable and anti-racist environment.

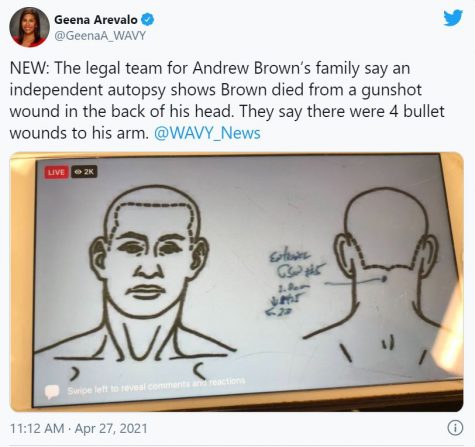

“[Racial bias] is an issue that has persisted for as long as America has existed and we cannot fix societal issues if we don’t face them head on,” said freshman James Torgerson. “Not only this, but there have been many murders of people of color in the recent weeks and months.”

It is no secret that conversations regarding race often make people uncomfortable. Americans are hesitant to discuss the issue because they are afraid to confront the fact that racism has infiltrated our society for centuries. This denial has led to a country filled with implicit racial bias and the lack of conversation, especially in the education setting, further allows these biases to perpetuate.

“Race is rarely talked about in the classroom,” said sophomore Aliyah Brown. “And whenever it is, it usually gets shut down pretty quickly.”

The article, “Why Conversations About Racism Belong in the Classroom” published by the USC Rossier School of Education acknowledges that “talking about racial identity and bias with children means acknowledging what children already know: people are different and the world is not colorblind.” Students recognize not only the differences between themselves and other students, but how their race affects how they are treated.

“I have experienced plenty of racial bias, [and] no one did anything about it,” said Brown. “In fact people laughed about it, I sat back and didn’t do anything because I was afraid of speaking up for myself in case I got myself into a situation I couldn’t get out of.”

The Century Foundation’s website asserts that “while talking about race can be emotional, uncomfortable, and frustrating, the work of embodying anti-racism in education must continue.” As students begin to grow in their knowledge, the education system must grow in their ability to hold open, honest conversations about race in America. This way, students of color can feel more seen in their classrooms and students of all races can work with educators to develop an anti-racist mindset.

“We have students of all ethnicities in every class which makes it very important to have discussions about race,” said freshman Riley Sievers. “Not only to let people express their opinions, but also to let others know how it feels to walk in their shoes.”

When educators and parents allow difficult conversations regarding race to become more mainstream and less taboo, students can learn what it means to be anti-racist. The task of combating racism requires much more than a recognition that racism exists and is morally wrong. Children are bystanders to racist words and actions every day and educators must emphasize the harmful effects these actions have on all students in order to prevent them in the future. Allowing these discussions where individuals examine implicit racial behaviors gives both students and teachers the opportunity to establish a more racially conscious foundation for the future.

“I believe [racial bias] should be talked about more due to it being a major issue in our day and age,” said sophomore Dawson Commodore.

On the other hand, some argue that conversations surrounding race only teach children to identify differences between them and their peers, in turn developing divisive viewpoints, and therefore these conversations do not belong in the classroom. The article “Critical Race Theory is Taking Over Virginia Beach Schools” by current School Board member Victoria Manning states that “the people who support this divisive ‘anti-racist’ theory are actually promoting racist practices that seek to divide rather than unite.”

“Although there can be good discussions [about racial bias] depending on the teacher, oftentimes it falls short of what is necessary,” said Torgerson.

Manning argues that teachers should not be forced to participate in training that promotes reformative ideas like the anti-racist mindset, much less include students in the conversation. This ideology is harmful, and completely disregards how pressing racial inequality is in society. This lack of conversation only dismisses the anti-racist mindset, creating the deeper divide.

These issues are far too crucial to ignore. It is up to each and every person to do the work to educate themselves and others to reverse inequitable behaviors and it is only appropriate for schools to open the discussion with their students in a mindful and appropriate way. This way all students can work together to understand and appreciate their similarities and differences.