When people think of the Civil Rights Movement, most think of MLK, Rosa Parks, Thurgood Marshall, or the Little Rock Nine— all big names taught in elementary school. However, most don’t know of the names that had just as big of an impact even closer to home. To our community, one such name is the Norfolk 17.

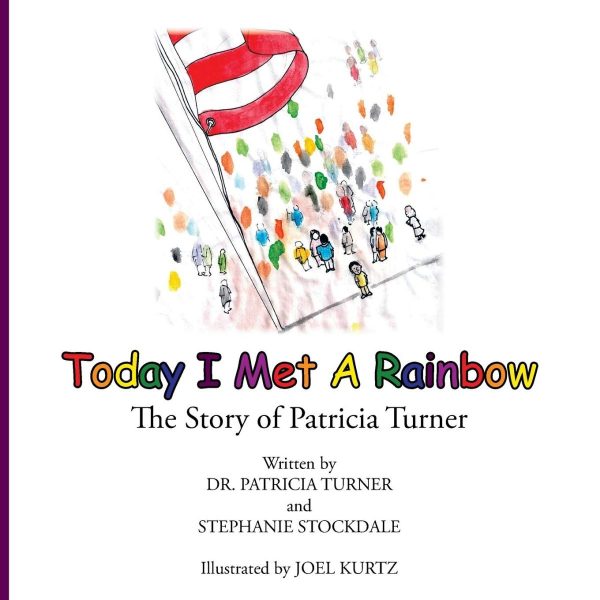

“We gave up our youth,” said Patricia Turner, a member of the Norfolk 17, in an interview with Wavy News (2019). “We didn’t go play. We had to study. We had to make sure that our grades were on track because we were carrying you [the future]. We were carrying each and every one of you.”

The Norfolk 17 were the first seventeen African-American students to integrate into all-white middle/high schools in the city they were named after. As a part of the desegregation movement following the ruling of Brown v. Board of Education, they directly faced opposition on both physical and legislative levels.

“I was knocked down the steps. I was spit in the face. My papers were taken from me and torn apart,” said Turner when describing her school experience after entering Norview Jr. High School (Wavy News).

Virginia had a strong reaction against integration, dragging its feet and prejudice to new lengths to prevent this long-awaited change. The state enacted a policy of Massive Resistance in 1956, which sought to block integration through various laws. For example, several schools were closed for varying periods of time right before enrolling black students.

“To this day, I don’t understand why Virginia would close their schools,” said Turner (Wavy News). “Norfolk particularly put out tens of thousands of white students. It makes no sense to me now.“

As Turner said, the Norfolk 17 were not the only ones affected by these school shutdowns. VA & U.S. History teacher W. Tabb Pearson’s mother was a white student part of the ‘Lost Class of 1959,’ the class which had their education displaced due to Virginia’s Massive Resistance policy.

“My mom went through that,” said Pearson. “She was a senior at Maury High School in 1959. That was the year they closed down the Norfolk schools [for the] first semester and reopened them around February.”

With such a wide impact, both then and now, the Norfolk 17 and members of other local desegregation movements have helped facilitate necessary changes in our education system.

“When we talk about [desegregation] in class, the way I [go about] it is I just have people look around the room,” said Pearson. “I point out to them that 75 years ago, you wouldn’t have seen integrated classrooms. It’s something we take for granted every day.”

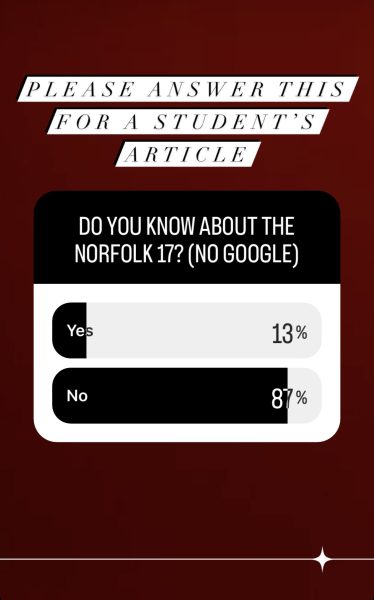

But despite its significance, many students today are completely unaware of the Norfolk 17.

“I didn’t [know about the Norfolk 17],” said senior Savannah Welge. “I would have never heard about these students if I hadn’t agreed to [an interview].”

A majority of students answered that they had not heard of the Norfolk 17 when questioned in an Instagram poll, and when asked in person, they were disappointed to not have heard of their story.

“[People should] learn about the Norfolk 17 because it’s important that we take into account the racial history in America,” said senior James Torgerson, who also did not know of the Norfolk 17 until interviewed. “[It should be taught in class for] at least elementary schools and middle schools.”

And Torgerson is not the only one who believes the story of the Norfolk 17 should be taught in schools.

“[Local desegregation movements should be taught in our cities’ schools] and not just in Norfolk,” said Pearson. “The same thing was happening here in Princess Anne County, Virginia Beach, a little bit after it happened in Norfolk. It’s not ancient history.”

Learning about local history is just as important as learning about national history. It teaches us about the events in the past that led to our home being the home we know it as.

The experiences of the Norfolk 17 allowed for our own school to have the diverse and inclusive community it has today.